By Heba Aly

Geneva prides itself on being a capital of multilateralism. And yet, most of the conversations here are about multilateralism’s demise. It is time to propose some solutions.

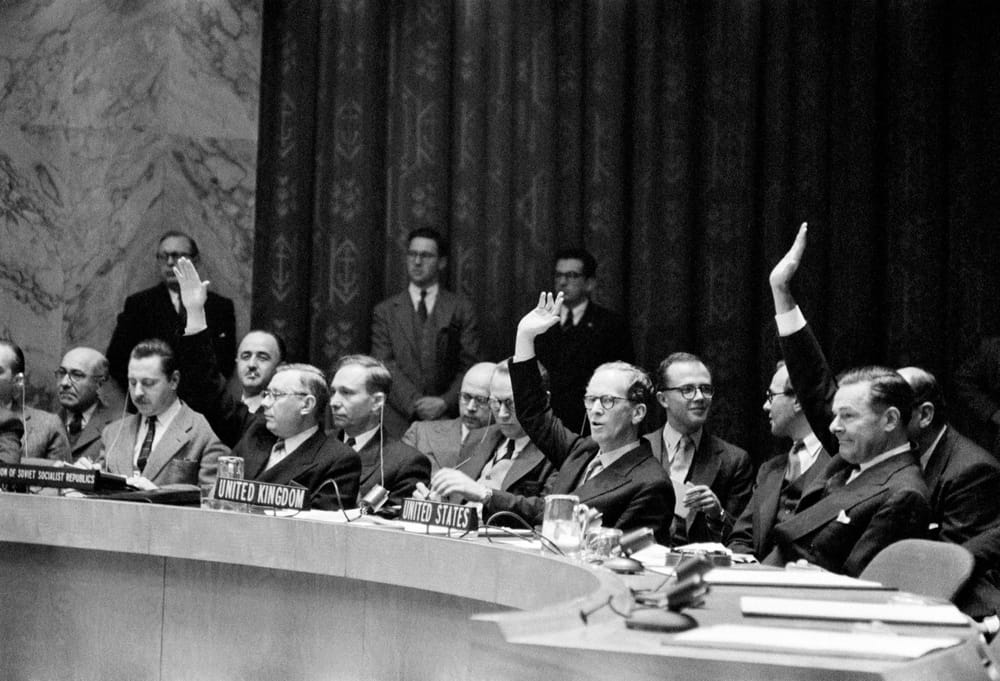

The multilateralism of today – embodied in the United Nations Charter – was conceived in 1945. As Stephen Heintz writes, the “logic” of international relations at the time was based on great power dominance, the primacy of the national interest, and imperialism, racism and patriarchy. It divided the world into “good guys” and “bad guys” (known in the Charter as “enemy states”) and into the powerful and powerless (one of the UN organs created by the Charter is the Trusteeship Council, mandated to oversee the transitions of colonies to independence).

One solution to making multilateralism more fit for purpose is to update its founding constitutional document – the UN Charter.

The UN Charter is one of the few universally accepted documents today. That is important at a time of such geopolitical fragmentation and polarisation.

But it was always meant to be a living document.

The Charter as a Living Document

At the international conference in San Francisco where the UN Charter was adopted, then-US President Harry Truman said: “This charter … will be expanded and improved as time goes on. No one claims that it is now a final or a perfect instrument. It has not been poured into any fixed mould. Changing world conditions will require readjustments.”

Nearly 80 years later, readjustments are long overdue.

In a forceful speech supporting reform of the UN Charter at the UN General Assembly in September 2024, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva said: “The Charter’s current version fails to address some of humanity’s most pressing challenges.”

The UN’s primary purpose was to ensure peace and security, but failures to stop wars in Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan and many other places show clearly that our global security system has broken down.

In addition, the Charter considers a third world war to be the main threat to humanity. Of course, this remains a risk, but so too are the existential threats posed by the planetary emergency and the uncontained growth of artificial intelligence, which are not mentioned in the 1945 text.

Furthermore, the Charter was initially adopted by only 50 countries – most of the African continent was still colonised at the time, only gaining independence in the 1950s-60s. Today, there are 193 independent countries in the world.

It centres the nation-state as the only player in multilateralism, whereas citizens, the private sector, and other non-state actors now play an increasingly important (in some cases, more important) role.

It cements power in the hands of five permanent members of the Security Council (P5), including the United Kingdom and France – two countries that, today, have far less power than, for example, India, Germany, Japan or Brazil. It centres the nation-state as the only player in multilateralism, whereas citizens, the private sector, and other non-state actors now play an increasingly important (in some cases, more important) role.

Article 109: A Charter Review Conference

So, what are pathways to change?

One is embedded in the UN Charter itself.

In 1945, a majority of the signatories to the Charter were opposed to the veto power given to the permanent five members of the Security Council. Nonetheless, as Mahmoud Sharei details, they agreed to sign on to “the promise of a more democratic UN in the future”.

This “qualified acceptance”, as Sharei puts it, was manifested in Article 109 of the Charter, which calls for a general conference to review the Charter within 10 years of the UN’s creation.

This promise has never been fulfilled.

The idea of reopening this most important constitution today may seem outlandish, but a one look at the Global Governance Forum’s proposals for what a “Second Charter” might resemble makes clear that there is much more to be gained than lost.

A revised Charter could help create a world that divides power equitably, better governs the climate crisis and other emerging threats, recognises our interdependence, and makes the UN more democratic.

Much should be maintained from the current Charter. Still, a revision could help create a world that divides power equitably, better governs the climate crisis and other emerging threats, recognises our interdependence, makes the UN more democratic by creating a world parliament akin to the European Parliament, and puts “We the Peoples” – rather than states – at the centre of global governance. While there are valid concerns about throwing the baby out with the bathwater, the mechanics of Article 109 provide a fail-safe mechanism against regression since a new Charter has to be ratified by a majority of governments, as well as the P5, to take effect (see here for more responses to typical concerns about Charter reform).

The long-standing push to reform the Charter has garnered increased momentum in the lead-up to the UN Summit of the Future in September 2024, in which all states adopted a series of commitments to renew multilateralism.

The idea is supported by Brazil, former heads of state, diplomats, and Nobel Laureates (from journalist Maria Ressa to former president of Costa Rica, Jose Maria Figueres, from former Kenyan Ambassador to the UN, Martin Kimani, to Chief Advisor and Premier Caretaker of Bangladesh’s Interim Government, Mohammad Yunus), and by the UN Secretary-General’s High-Level Advisory Board on Effective Multilateralism, which called for invoking Article 109 in its landmark report.

A newly launched UN Charter Reform Coalition is now mobilising member states to call a general conference to review the UN Charter. It aims to attract more than 100 civil society organisations and six-member state champions to its cause in 2025.

This effort will face many obstacles, but given the large swath of the world that is not well-served by the current world order, a new system to govern the world is inevitable.

“I have no illusions,” President Lula acknowledged in his speech, “of the complexity of a reform like this, which will face crystalised interest in maintaining the status quo. It will require enormous negotiation effort. But that is our responsibility.”

Lula went on: “We cannot wait for another world tragedy, like World War II, to only then build a new governance on its rubbles.”

There is also a more concrete incentive for those who hold power in the current international architecture to engage in reform. They are well served by renegotiating the distribution of power in the UN Charter now while they still have a relative power advantage. Shifts in real power are already underway and likely to be accelerated by Donald Trump’s presidency of the United States. In the next 10-20 years, new powers could simply create their own institutions, or, at the very least, have enhanced negotiation power.

What role for Geneva?

Switzerland’s total contribution of $805 million to the UN in 2023 made it the 13th-highest contributor to the organisation. Given its significant investment, Switzerland has a stake in making the UN more effective.

Geneva, in particular, is home to a UN headquarters, 181 states, 40 international organisations (including specialised UN agencies like the UN Refugee Agency and the World Health Organization), and 461 NGOs, creating fertile ground for multi-stakeholder debate about the underpinnings of the international relations of the future.

In the home of human rights, humanitarian and health policymaking, actors in Geneva are more intimately acquainted with the real-life impacts of breakdowns in global governance than in New York.

Compared to the UN’s main headquarters in New York, Geneva’s less politicised environment lends itself to incubating bold ideas for the future of multilateralism. In the home of human rights, humanitarian and health policymaking, actors in Geneva are more intimately acquainted with the real-life impacts of breakdowns in global governance than in New York. Perhaps as a result, ambassadors here seem more willing to serve collective – rather than national – interests.

Normative improvements to the UN Charter will have to happen sooner or later. Switzerland’s historical neutrality and Geneva’s international mosaic allow both Switzerland and the “International Geneva” ecosystem it nurtures to play a leadership role in breathing new life into this most important of documents.

About the Author

Heba Aly is the coordinator of the UN Charter Reform Coalition, a senior advisor at the Coalition for the UN We Need, and the former CEO of The New Humanitarian.

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Geneva Policy Outlook or its partner organisations.