By Marie-Laure Schaufelberger

The Financial Stability Board declared climate change a system-wide risk years ago. In March 2022, the Network for Greening the Financial System (regrouping 116 supervisory authorities - including the FINMA or The Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority and the Swiss National Bank) publicly stated that “nature-related risks could have significant macroeconomic and financial implications.” Over the last decade, humanity has gone from denial to accepting that it is time for action. There has been a shift from the narrow focus on climate to one that encompasses all planetary boundaries; and from trying to assign blame to accepting we all have a role to play.

The transition to a more resilient economy requires far more investment than it receives today, which implies that those allocating capital must redefine their responsibility to society.

The challenge that governments, companies, regulators, and civil society now face is how to collectively implement the transition to a more resilient and sustainable economy and at what pace. Change is daunting and difficult, but also necessary for realising better outcomes and easier to achieve when working towards a shared goal. One thing is certain: the transition to a more resilient economy requires far more investment than it receives today, which implies that those allocating capital must redefine their responsibility to society.

The greatest market failure of all time

The ecological collapse that we could witness over the next decades is the result of the greatest market failure of all time. For decades, we have essentially benefitted from a “free lunch” on the back of our planet. And investors know there is no such thing as a free lunch.

In financial terms, humanity has accrued enormous debt vis-à-vis essential ecosystem services – the carbon and water cycles, land systems and biodiversity. We have responded by requesting multiple extensions on this debt, rolling it further into the future. Planet Earth is now giving us increasingly frequent margin calls in the form of climate chaos: extreme heat, forest fires, floods and drought. Analogous to financial debt, the longer we put it off, the higher the ultimate cost. Unlike financial debt, there is no central bank for nature. No institution can intervene overnight to drawdown carbon from our atmosphere, print more healthy soil, or inject more water where it is needed the most.

Declaring bankruptcy won’t solve a planet that is becoming increasingly hostile to human life. If we continue to delay decisive action, it will affect the entire system. Amidst the current macro-volatility characterised by inflation, disrupted supply chains and geopolitical conflicts, it is easy to forget that the earth’s climate is quite indifferent to humanity’s economic or political struggles.

The role of the investment management industry

The effects of severe climate change and nature loss cannot be hedged or diversified away.

According to the OECD, the gap in reaching the Sustainable Development Goals in developing countries has increased by 56% post-Covid, totalling USD 3.9 trillion in 2020. In developed (OECD) economies, this spending competes with healthcare and mounting defence budgets. In developing countries, the double burden of debt and climate adaptation will be untenable in the absence of increased capital flows. The vast pools of capital managed on behalf of savers all over the world will have to play a part in achieving this goal, notably, the 80% held in high-income countries. Governments alone will not be able to secure an accelerated transition and build more resilience, although their role will be crucial in setting policy and framework conditions for private green investment, carbon taxation, credible emissions trading and redirecting subsidies.

The effects of severe climate change and nature loss cannot be hedged or diversified away. As universal owners, investment managers and asset owners are exposed to a representative slice of the economy and all its sectors, they have a great opportunity to act responsibly, and an enormous risk if they do not.

Despite the science, some still argue that incorporating environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors into decision-making falls outside the fiduciary duty to deliver financial performance to clients. This betrays a misconception of both the role of the investment management industry and the scientific reality. One of the core functions of the active asset management industry is price discovery. It involves identifying pricing inefficiencies through data collection, filtering and analysis to derive actionable investment insights. It is about having the discipline to do this in a robust and repeatable way, over time, integrating relevant information with material impact on the price of financial assets. We know that the current prices are distorted because externalities (pollution, emissions, use of natural resources) are not adequately reflected in markets. Portfolios are inevitably exposed to growing global economic costs, which could materialise in investee companies and markets as insurance premiums, taxes, inflated input prices, stranded assets, increased litigation risks and the physical costs associated with natural disasters. This information is increasingly sanctioned by the market.

The role of active managers has not changed, but the inputs required to deliver optimal risk-adjusted returns have. Now that we know the facts that help complete the full picture, environmental and social considerations simply cannot be ignored.

Additionally, efficient allocation of capital to issuers with low or diminishing externality costs (such as providers of green technologies or issuers that are transitioning from highly carbon-intensive operations towards a net-zero state) should provide protection over the long term and generate better-quality and more predictable profitability. Ultimately, investors should benefit from the more resilient system that they help support and build. Consequently, responsible investors cannot simply look at the risks to their assets, but must also be concerned with the impacts of capital allocation decisions on environmental and social outcomes.

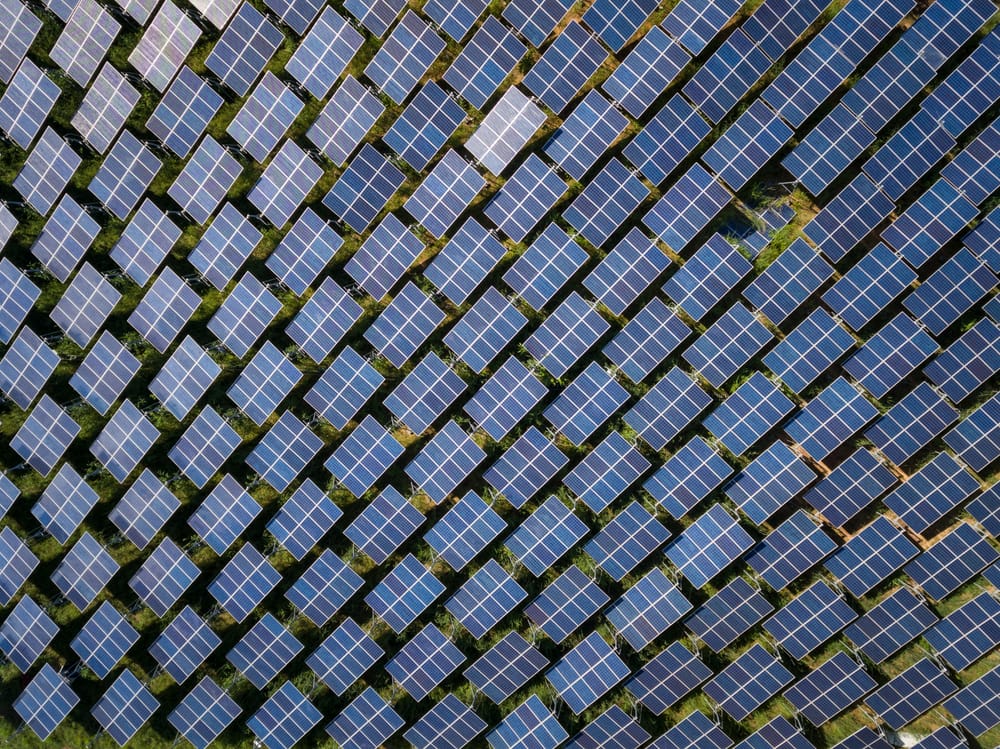

As stewards of long-term savings, investors can do three things to support the transition to a low-carbon and nature-positive economy. First, they can allocate capital to the companies developing the technologies and services that reduce the pressure on ecosystem services and build circularity. Second, they can direct capital towards companies whose operations are aligned with science-based environmental targets. These are the companies that will roll out the solutions available to reduce the impact of all human activities. From the buildings we live in, to how we travel and feed ourselves, well over 90% of the economy needs to transition. Third, investors can and should engage for change. As investors, selling a polluter with transition potential to another buyer does not reduce emissions released into the environment. There will always be speculators willing to take on additional risk for greater potential return in the short term. Numerous studies have shown that engagement is more effective than exclusion at changing corporate behaviour.

Collaboration and a systemic approach are key

Engagement is far more effective when led by a local investor with the backing of a larger group of diverse stakeholders. The Climate Action 100+, a collaborative investor initiative, which has gathered backing from USD 68 trillion in assets to engage the world’s 170 largest corporate greenhouse-gas emitters, is a great example of this new model. Data and insights from NGOs, catalytic capital from foundations, trillions in committed capital from investors, and the Paris Agreement policy framework were all needed to bring the CA100+ to life. Initiatives on water and nature are following suit.

The more we understand environmental issues, the clearer it becomes that we must provide transition pathways to all, not just the affluent and the activist.

We need more action of this kind, with far more capital flowing to where it is needed most. This is where Geneva – a city where different ideas and beliefs have co-existed in open dialogue for centuries – has a key role to play. A leading centre for investment management globally, it is home to the United Nations, 179 foreign missions, 37 international organisations, 400 NGOs, and one of the highest concentrations of philanthropic foundations anywhere in the world. It has also been at the forefront of human rights and establishing the norms and standards required for strong social foundations. This consideration of social factors is key. The more we understand environmental issues, the clearer it becomes that we must provide transition pathways to all, not just the affluent and the activist. There will be no green transition in the absence of a new social contract.

This Geneva ecosystem – with its combination of knowledge, capital and convening power – has a unique ability, and responsibility, to take bold action to support the transition current and future generations deserve.

About the author

Marie-Laure Schaufelberger is Head of ESG and Stewardship for the Pictet Group.

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Geneva Policy Outlook or its partner organisations.