By Pedro Conceição

One of Geneva’s most well-known figures, Jean- Jacques Rousseau, reflected upon how humans’ alienation from each other, fuelled by progress, paralleled their alienation from nature. His view that progress corrupted while nature healed, echoed through the centuries, from the Romantic artistic era, to strands of contemporary ecological consciousness and nature conservation movements. It might be argued that prevalent framings of sustainability challenges, which pit humans as inevitable destroyers of nature that need to be reigned in through fear or limits, are yet another echo of Rousseau’s view.

But perhaps there is another reading of Rousseau’s reflections. He was not saying “humans are bad” and “nature is good”. Humans, in what he termed a “natural state,” were also inherently good and, indeed, one with nature. It was progress that corrupted the relationships, both of people with one another and between humans and nature. This reading of Rousseau drives us to examine the kind of progress that is being pursued today and how. It takes us to the realm of human choices and how to shape them to achieve desirable goals.

Progress in human development occurs when capabilities expand so that, over time, more and more people live their lives to their full potential. Progress in human development is an open-ended journey powered by the aspiration to improve people’s lives.

So what goals are desirable? And what is progress? The human development approach is one of the many ways of addressing these questions. The goal in human development is to enable people to live their lives to their full potential, which means people’s ability to be and do what they value and have reason to value. The focus of human development is on the broad set of capabilities that shape the extent to which this goal can be pursued, where capabilities are factors like being healthy or able to access knowledge and information. Resources and income can be important, but instrumentally for capabilities, not as goals in themselves. Progress in human development occurs when capabilities expand so that, over time, more and more people live their lives to their full potential. Progress in human development is an open-ended journey powered by the aspiration to improve people’s lives.

Lofty ideas of progress, no matter how they are defined, rarely go anywhere without another important ingredient: metrics to assess changes over time and to evaluate relative performance across jurisdictions. That is why the very first Human Development Report (HDR) in 1990 introduced both the concept and the measurement of human development. It proposed the Human Development Index (HDI) to capture a basic set of capabilities measured by achievements in standards of living, health, and education. The HDI is one, but not the only, metric of human development. Over the years, UNDP’s Human Development Report Office (HDRO) has introduced several other metrics, including the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI). The need for several metrics relates in part to the broad and multidimensional characteristics of the human development approach, which make it impossible to have only one index to capture all relevant dimensions at the same time. But metrics are not only varied but also dynamic, since they need to reflect new aspects relevant to pursuing progress in the form of advancing human development.

One of the aspects that has inspired innovations in metrics of human development in HDRO is trying to understand how prospects for human development are shaped by planetary changes, like climate change. The HDRO and Climate Impact Lab Human Climate Horizons data platform provides scenarios on the evolution of factors like mortality rates and labor supply from now up to the end of the century at a subnational level for the entire world. It also provides scenarios for how the very pursuit of progress in human development can drive those very planetary changes, for people and other forms of life on Earth. This theme was also explored in the 2020 HDR, which introduced the planetary pressures-adjusted HDI. Often, pursuing progress, however defined, results in negative unintended consequences, and the pursuit of advances in human development is no different. This is why HDRO has devised a metric to account for the unintended consequences of patterns of pursuit of advances in human development that are resulting in greenhouse gas emissions and material use that are driving planetary change.

Progress has drawbacks, but the implication should not be that just because we find some of the implications of progress to be negative, we should abandon its pursuit. The unintended negative consequences of pursuing the advancement of human development do not nullify the value of the aspiration for people to lead better lives, today and in the future. In fact, why should we not turn this logic around, and use these aspirations for a better world for people to power a better world for all living beings while ensuring the integrity of ecosystem functions?

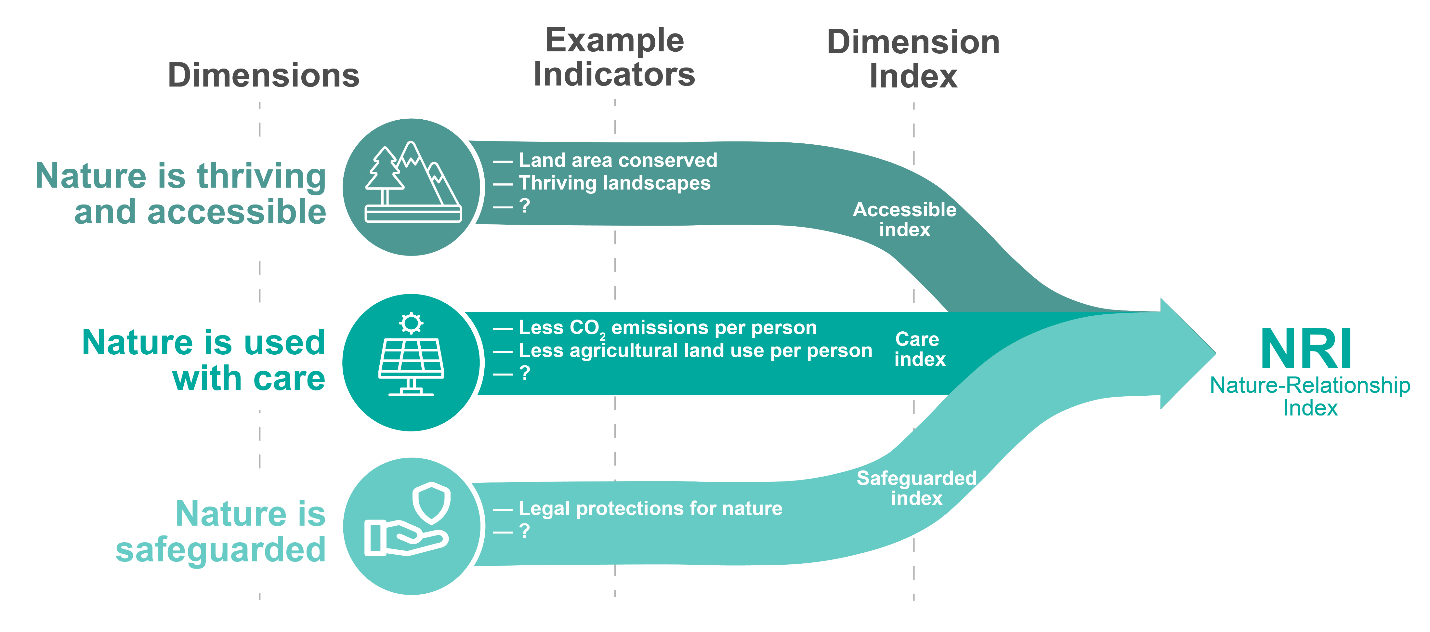

HDRO, along with an interdisciplinary group of scholars and practitioners, has been reflecting on how to conceptualise and eventually construct a metric that could assist us in figuring out if the power of human aspirations can be mobilised to propel sustainable futures for people and planet. The conceptual approach and associated metric (a Nature Relationships Index – NRI) was proposed in a paper published in Nature in June 2025 that inspired an opinion editorial in the Financial Times in August of 2025. This approach intends to define a limited set of dimensions that could capture the extent to which people are in a good relationship with nature. Taking inspiration from the HDI, the conceptual approach of the NRI identifies three dimensions, assessing whether: nature is thriving and accessible, nature is used with care, and nature is safeguarded. The dimensions, indicators, and indices of the NRI are illustrated in Figure 1.

Let us be clear: the pursuit of progress has often led humans to be destroyers of nature. But they don’t have to be so. And processes of individual and public reasoning can be mobilised to change the way in which progress is pursued without giving up on the aspiration of progress itself.

The dimensions are meant to account for clear and intuitive aspects of the way in which people relate to nature and, eventually, to have indicators that can quantify that. To take an example from the HDI, one of the dimensions is “a long and healthy life”. This is something that people universally understand, relate to, and consider to be desirable. Then, as a next step, as a proxy indicator, life expectancy at birth was identified. Currently, the three dimensions of the NRI are being subject to a robustness test to see if they meet the need to be understandable and easy to communicate. A further step, currently under development, would identify proxy indicators (those identified in the figure for illustrative purposes only). The third step is to transform each of the indicators into an index that can then be aggregated into a single number, resulting in the NRI.

The metric borrows very much from Rousseau, and the importance he attributed to relationships between people and between people and nature. The proposal for the NRI is meant to affirm that humans are not inevitably destroyers of nature as they pursue progress in advancing human development. Let us be clear: the pursuit of progress has often led humans to be destroyers of nature. But they don’t have to be so. Processes of individual and public reasoning can be mobilised to change the way in which progress is pursued without giving up on the aspiration of progress itself. And without assuming that the only way in which humans act is when their back is against the wall, as Malthus defended, and that, therefore, we need to scare people with the prospect of imminent catastrophe to trigger action on sustainability. This is not to deny that we confront a climate crisis and that prospects will be dire if we don’t change our ways. However, the more pressing focus today should be on how to trigger that change, instead of having more information about those dire consequences, even though the latter is also important.

The NRI is thus meant to inspire people, decision makers, and researchers to harness human aspirations for a better future to make choices that can lead to nature and humans thriving together. That will imply making changes, but the idea would be to change in ways that are motivated by hope, rather than fear.

The NRI is thus meant to inspire people, decision makers, and researchers to harness human aspirations for a better future to make choices that can lead to nature and humans thriving together. That will imply making changes, but the idea would be to change in ways that are motivated by hope, rather than fear. This is particularly important because the changes required today are not only about protecting the local or even national environment. Change is needed in ways that go beyond what any single country, no matter how powerful, or even a group of countries, can do on their own. Dangerous planetary change is a shared problem for all of us living on Earth. There are many ways in which countries’ interdependencies can be managed through policy choices – in trade, capital flows, migration – but no such options are open when we confront the reality of living on a shared planet. Only multilateral approaches can work, and were Rousseau to visit Geneva today, he would be proud to see a hub of multilateral organisations supporting these processes, ranging from producing and analysing the data that is so crucial for metrics of progress to convening decision makers to craft the collective actions required to address planetary challenges. The human development approach, its concepts, and metrics, will hopefully continue to play a role in supporting these processes going forward – and will continue to need to change and innovate to address the next generation of unintended consequences that will inevitably emerge. But one thing is clear: we should not give up on mobilising human aspirations for a better world to help us address sustainability challenges.

References

Ellis, E.C., Malhi, Y., Ritchie, H. et al. An aspirational approach to planetary futures. Nature 642, 889–899 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09080-1

About the Author

Pedro Conceição is the Director of the Human Development Report Office at the United Nations Development Program.

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Geneva Policy Outlook or its partner organisations.