By Lucile Maertens, Zoé Cheli, Adrien Estève and Lorenzo Guadagno

In a time of escalating crises, global trend of democratic backsliding, backlash against multilateralism, and withdrawal of multilateral funding, International Geneva continues to grapple with overlapping challenges. With increased competition between policy areas for political attention and limited funding in a fragmented multilateral system, long-term issues such as responding to climate change and upholding human rights run the risk of being deprioritised. This trend emerges from the tendency of multilateral organisations to resort to a ‘first things first’ approach when faced with a crisis, mobilising resources to assist the most affected and shifting priorities towards addressing the emergencies.1

Such a competitive environment prompts an introspective, but essential question: how do Geneva-based organisations react to coinciding crises, political backlash, and threats to their survival? In other words, how do Geneva-based international organisations maintain the relevance of their mandates? A framework to respond to this question emerges from the concept we coin as ‘agenda keeping’: the process of maintaining an issue as a priority for action amid other competing problems. By deploying different agenda-keeping strategies, actors in International Geneva attempt to ensure visibility for overshadowed issues while preserving their relevance.

Agenda-Keeping Strategies in International Geneva: A Sectoral Analysis

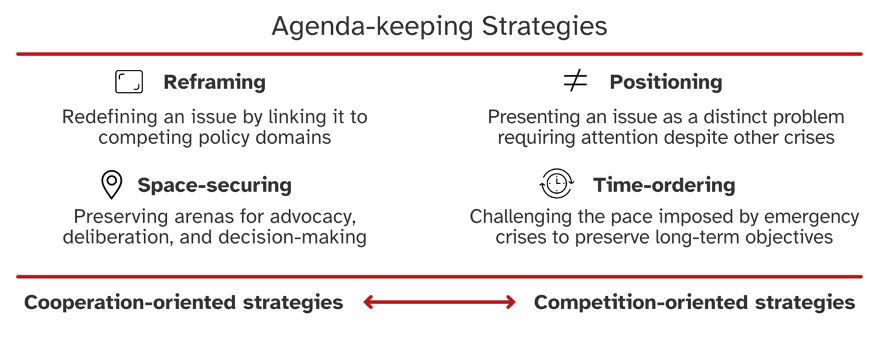

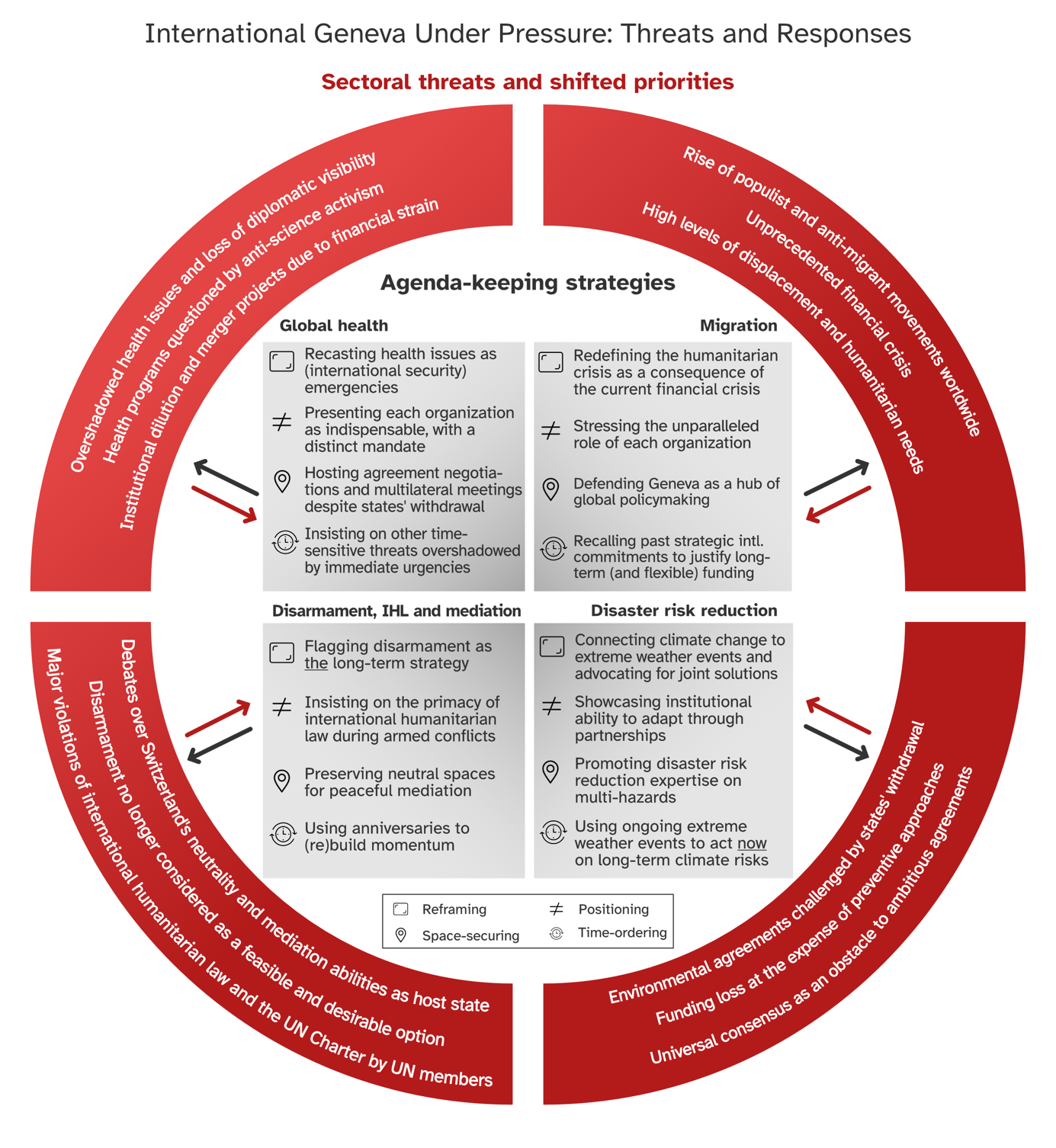

Geneva-based actors respond to the current crisis and the multiple threats each policy sector faces by employing four different agenda-keeping strategies. First, organisations use ‘reframing’ techniques to redefine issues that they work on by linking them to competing policy domains. At the same time, organisations engage in ‘space-securing’ by preserving arenas for advocacy, deliberation, and decision-making. These first two strategies may facilitate better cooperation as they offer more opportunities for organisations to collaborate in complementary ways. Conversely, the other two strategies adopted by international organisations may inadvertently intensify competition for resources, both material and symbolic: reorienting their ‘positioning’ to present an issue as a distinct problem requiring attention despite other crises, and ‘time-ordering’, by challenging the pace imposed by emergency crises to preserve long-term objectives. To illustrate how Geneva-based organisations are employing these agenda-keeping strategies, it is worth examining four examples.

Actors in the global health community of International Geneva, faced with challenges such as the loss of diplomatic visibility, anti-science activism, and institutional dilution resulting from major financial strain, actively employ agenda-keeping strategies to ensure their relevance. These actors reframe their priorities by recasting health issues as emergencies, linking them, for instance, to international security. The World Health Organization (WHO) has notably described the budget crisis as a threat to global health security, arguing that funding is “not only a moral imperative–it is a strategic necessity”. Global health actors also engage in ‘space-securing’ by continuing to host multilateral negotiations, as portrayed by the adoption of the Pandemic Agreement at the World Health Assembly in Geneva in May 2025. In doing so, they preserve a diplomatic platform for global health cooperation despite the US withdrawal from the WHO. At the same time, global health actors are strategically positioning themselves as indispensable, with distinct mandates. When the UN80 Initiative proposed merging UNAIDS with the WHO, the former rejected such merger, defining its mandate as one “fill[ing] policy gaps and pick[ing] up where WHO [can] not.” UNAIDS also reframed AIDS as a renewed emergency, no longer a pandemic getting under control, but a “ticking time bomb”, warning about millions of projected new infections and deaths if services were to collapse following defunding of AIDS response, an instance of a ‘time-ordering’ strategy.

Actors in the global health community of International Geneva, faced with challenges such as the loss of diplomatic visibility, anti-science activism, and institutional dilution resulting from major financial strain, actively employ agenda-keeping strategies to ensure their relevance.

Actors working on migration-related issues in International Geneva position themselves similarly. Faced with a rise of populist and anti-immigration movements, an unprecedented financial crisis, and high levels of displacement and humanitarian needs, actors like the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) redefine humanitarian crises as consequences of the financial crisis. The IOM flagged the urgency of addressing migration as, simultaneously, a strategic issue for all countries, a humanitarian concern, as well as a development and security matter. It positions itself as an actor with an unparalleled ability to work flexibly and effectively across the Humanitarian-Development-Peace nexus, supporting programmes that align with the needs of different governments. Similarly, the UNHCR signaled the need to sustain refugee protection as both a legal and humanitarian obligation and as a specific area of concern for countries all over the world, requiring continued political and financial commitments in the face of considerable levels of displacement. In doing so, the UNHCR ‘time-orders’ past strategic commitments to justify long-term funding. These positioning strategies acquire particular significance as a potential merger of the two agencies is also being discussed under the UN80 Initiative.

While major violations threaten international humanitarian law and aggravate human suffering worldwide, Geneva-based organisations continue to promote peaceful mediation and disarmament by adopting agenda-keeping strategies.

While major violations threaten international humanitarian law and aggravate human suffering worldwide, Geneva-based organisations continue to promote peaceful mediation and disarmament by adopting agenda-keeping strategies. These actors present mediation and disarmament as the solution for a sustainable future and reframe them in connection with other burning issues like AI or space security. The systematic mention of international humanitarian law, as ensured by the Swiss delegation at the UN Security Council, aligns with efforts to position humanitarian assistance above politics. Milestones such as the 75th anniversary of the Geneva Convention or the 80th year of the Hiroshima bombing serve as platforms to build momentum and maintain political attention. International Geneva also seeks to remain a credible and relevant space for mediation by offering to host critical negotiations, such as those concerning Iran’s nuclear programme.

The multilateral environmental agenda has also come under pressure, particularly amid the upcoming formal US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, effective 27 January 2026. The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) illustrates how UN entities strive to keep environmental issues on the agenda, despite the loss of funding, withdrawal of states, and a lack of consensus for ambitious agreements. During its 2025 Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction, hosted in Geneva, the UNDRR recalled the link between climate change and extreme weather events such as droughts and wildfires, promoting common solutions through “comprehensive risk management strategies” and reframing the DRR agenda to advocate for joint solutions. It also emphasised its partnerships with regional institutions like the European Union on resilience, positioning itself as an agency uniquely able to adapt its procedures to the crisis. In collaboration with the International Science Council, it secured space for its own expertise on multi-hazards, invoking the 2025 heat waves to advocate for improved risk governance to address climate-related hazards, framing heat waves as “more than a seasonal inconvenience”.

Figure 2 summarises the different agenda-keeping strategies in the areas of global health, migration, international humanitarian law and disarmament, and disaster risk reduction.

Conclusion

While actors in International Geneva navigate through overlapping crises, agenda-keeping emerges as a strategic tool to assert their relevance and ensure that the focus on long-term priorities is not lost. As polarisation increases and funding challenges worsen, Geneva-based actors are likely to continue engaging in agenda-keeping in 2026 to preserve at least minimal visibility to the issues they promote, at times creating new opportunities for cooperation, and at others reinforcing existing inter-organisational competition. They may oscillate between politicisation, taking bold positions when support seems already lost, and depoliticisation, when apolitical claims serve pragmatic logics of action. They may also seize key political moments and critical decision-making spaces, while adopting a wait-and-see posture when possible.

International Geneva could position itself as the global capital for agenda-keeping; yet ensuring that the major challenges facing people and the planet remain a priority should go hand in hand with creativity and inclusion in the necessary transformations of global governance.

Overall, agenda-keeping is not only a matter of mandate and relevance preservation, but also a process through which long-term priorities are proactively selected and purposely reshaped. International Geneva could position itself as the global capital for agenda-keeping; yet ensuring that the major challenges facing people and the planet remain a priority should go hand in hand with creativity and inclusion in the necessary transformations of global governance.

About the Authors

Lucile Maertens is the Co-Director of the Global Governance Centre and Associate Professor in International Relations and Political Science at the Geneva Graduate Institute.

Zoé Cheli is a project officer at the Competence Centre in Sustainability (CCD) at the University of Lausanne.

Adrien Estève is is Associate Professor in Political Science and International Relations at the University of Clermont Auvergne (Michel de L’Hospital Center, UR 4232).

Lorenzo Guadagno is a Project Coordinator (PAMAD) at the Secretariat of the Platform on Disaster Displacement.

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Geneva Policy Outlook or its partner organisations.